Millers Falls Mfg. Company: 1868 to 1873

Organization and site preparation

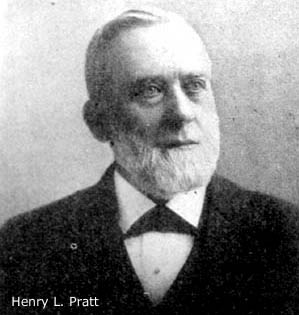

When the waterpower shortage at Gunn, Amidon & Company precluded an expansion of the factory, an infusion of capital was in order. The company’s situation came to the attention of Henry L. Pratt, a prosperous lumber dealer who had returned to the area after operating a furniture business in Detroit. Pratt recommended the firm relocate to Grouts Corner, a nearby village and a stop at the junction of the Vermont & Massachusetts and the New London Northern railroads. Consisting of little more than an inn and a few houses, Grouts Corner was located on the Millers River at a spot where the stream dropped seventy feet over a short series of rapids. Gunn and Amidon, impressed with the potential of the site, joined Pratt in organizing the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, an enterprise established “for the purpose of manufacturing hardware and lumber at Millers Falls.” Henry Pratt became the firm’s first president; Gunn and Pratt served as directors.(1) On September 21, 1868, notice of the incorporation appeared in the Greenfield Gazette and Courier. The newspaper reported that $100,000 in stock had been issued, waterpower rights had been secured and 200 acres of land had been purchased.

When the waterpower shortage at Gunn, Amidon & Company precluded an expansion of the factory, an infusion of capital was in order. The company’s situation came to the attention of Henry L. Pratt, a prosperous lumber dealer who had returned to the area after operating a furniture business in Detroit. Pratt recommended the firm relocate to Grouts Corner, a nearby village and a stop at the junction of the Vermont & Massachusetts and the New London Northern railroads. Consisting of little more than an inn and a few houses, Grouts Corner was located on the Millers River at a spot where the stream dropped seventy feet over a short series of rapids. Gunn and Amidon, impressed with the potential of the site, joined Pratt in organizing the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, an enterprise established “for the purpose of manufacturing hardware and lumber at Millers Falls.” Henry Pratt became the firm’s first president; Gunn and Pratt served as directors.(1) On September 21, 1868, notice of the incorporation appeared in the Greenfield Gazette and Courier. The newspaper reported that $100,000 in stock had been issued, waterpower rights had been secured and 200 acres of land had been purchased.

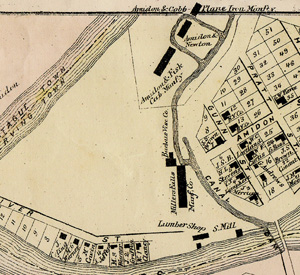

James Moore became an investor in the company by virtue of his ownership of the tract where the new factory was to be built. James and his father, Oliver, had been trying to find a developer for the site for at least a dozen years, having gone so far as to commission and distribute a promotional map of the tract in 1856.(2) Located on a horseshoe bend of the river, the heavily wooded, one-hundred-acre location was ideally suited to its purpose. Lumber for construction could be sawn from timber on site, and the extreme curvature of the river made it a relatively simple task to dig a mill canal across the neck of what was almost a peninsula. From the outset, the directors understood they were not only building a mill and hardware manufactory but were developing an industrial site with a surplus of highly prized waterpower. The organizers estimated Millers Falls Manufacturing would need one-fourth of the output of the dam and expected other businesses—each with a millrace connected to their canal—would purchase the rest. Then too, the company would be in the residential real estate business; the directors had purchased enough additional land to start a housing development.

The construction site was already home to a blacksmith shop and a sawmill. James Moore wrote to his parents on October 27, 1868, mentioning his eldest son James would be sawing lumber for the company.

We have not made much mark yet in our new enterprise, but the man who has contracted to dig the canal and wheel pit & lay the foundations for the factory &c is coming on today. The Co. took possession of the mill a week ago last Monday. They are going to take out the old Robins sawmill and put in another new one as there seems to be much repairing on the old one including building a new carriage to lengthen out and will not be what they want with water power. They concluded to sell the old mill. James has taken the contract for doing the sawing for the Co. until the first of next Aug. (when the Co. intends to get water on to the mill) for $250 per M. The Co. has contracted to have three houses built this fall & sold three building lots to another party who has agreed to put on three houses early next spring.(3)

Two months later and just six months before his untimely death, Moore continued his report to his parents, using the pronoun we when referring to the company.(4)

Our Canal is dug from the Blacksmith Shanty, through as far as it is going & quite a piece of the race is also dug. You understand, I suppose, that the Canal is dug north along at the foot of the “big bank”, instead of down the river as per map. We get two privileges going that way, of 16 feet each, aggregate 32 feet & the water runs off under the Lugar place bank. We save as the fall from the traveled Bridge at the Corner to the head of the Island. We have three Houses building & three more cellars are dug & Ho. drawn. I am doing the logging & James doing the sawing. We have got a petition for a Road & Bridge with about 100 names on it & we shall probable (sic) get it laid and built the coming season. We have been talking about buying Alden Grout's place, but he has got his figures up to $10,000 & I hardly think we shall make a trade. We now have the refuse of it for that price for 10 days, which has nearly run out. We are trying to get some Brick made at Northfield Farms, a man here yesterday to look about it. A kiln could be put up right by the Depot, a good place for a yard, Clay & Sand handy. We were hoping to find some clay near enough to draw on to our own ground here & make & burn them right on the ground but could not find any nearer than the Asabel Stevens place or thereabouts.

P.S. The Stock Holders of the Millers falls Manufacturing Co. are anti-Tobacco, anti-rum, to a man. A thorough temperance corporation...(5)

On December 31, 1868, the day after James Moore finished his letter to his parents, disaster struck the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. A fire gutted the North Parish plant; only the office area was spared. All the firm’s manufacturing equipment was destroyed, and production ceased. The editor of the Greenfield Courier & Gazette suspected arson.

The place where the fire was discovered was separated from the boiler room by a stone wall or partition, where it would not have been likely to have caught from any accident. The place, too, was the best that could have been selected by a villain for his foul purpose, as the fire could communicate with each story of the building by means of a slide-way, where chips and waste lumber were dropped into the wood-room below.(6)

Although insurance covered just half of the $40,000 loss, work to secure temporary quarters began immediately. Within two weeks, the firm was installing equipment in rooms rented from the Greenfield Tool Company. As the new quarters were too small, work on a temporary building at the Greenfield Tool site began without delay. Construction of the forty-foot-long wooden structure started on January 25th, a Monday morning. By Wednesday evening, the building was up, the siding in place, the windows set and the power shafting installed. On that Saturday—six days after the building was started and just four weeks after the fire—a full workforce was in place, building braces. The disaster at the North Parish plant marked the end of the company’s involvement in the wringer repair business. Chamberlain & Whitmore, a local firm, bought the remnants of the operation.

Building the factory

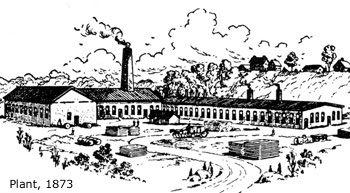

In April 1869, Millers Falls Manufacturing made the plans and specifications for its Grouts Corner factory available to bidders. The planners estimated a quarter of a million bricks would be needed to complete the main building. The proposed structure, Three feet long and fifty feet wide, was considered fireproof by the standards of the day. For additional safety, the plant’s boilers, used to produce steam for heating the structure, were to be housed in a wing projecting at a right angle from the main building. Running water was to be available throughout the structure. Work on the factory began immediately after the bidding. Local residents, skeptical the enterprise would succeed, at first refused to fund a bridge to the site. A traditional covered span was erected only after Millers Falls Manufacturing agreed to put up one-half of the cost.

A dam, twelve feet tall and 165 feet long, was built on one of the series of falls and created a pond substantial enough to deliver 800 horsepower to its downwater users. (The company had originally hoped for 1500.) Millers Falls Manufacturing required less than half of the output. There was little worry the upper limit of the dam’s capacity might be reached—the company owned the rights to the two remaining falls in the series. In lieu of a traditional mill wheel, a modern water turbine, manufactured in the nearby town of Orange by Hunt, Waite & Flint, was installed to power the factory.

The move to the plant took place in the winter of 1869 and 1870. In January, fifty workers took up positions in the new factory. Although some chose to commute from Greenfield, the majority relocated, and the housing situation in Grout’s Corner grew desperate. Millers Falls Manufacturing leased the hotel owned by the Vermont & Massachusetts Railroad Company and refurbished it to domicile some of the workers. As other buildings became available, the company rented them and converted them into tenements. In spring, the hilltop east of the plant became a prime target for development and was soon home to Amidon, Gunn, and Pratt Streets. The manufacturer made its presence known in other ways—a petition to rename the place Millers Falls was circulated, and by spring, the post office had been renamed. It took several years for the local railways to adopt the new moniker.

The move to the plant took place in the winter of 1869 and 1870. In January, fifty workers took up positions in the new factory. Although some chose to commute from Greenfield, the majority relocated, and the housing situation in Grout’s Corner grew desperate. Millers Falls Manufacturing leased the hotel owned by the Vermont & Massachusetts Railroad Company and refurbished it to domicile some of the workers. As other buildings became available, the company rented them and converted them into tenements. In spring, the hilltop east of the plant became a prime target for development and was soon home to Amidon, Gunn, and Pratt Streets. The manufacturer made its presence known in other ways—a petition to rename the place Millers Falls was circulated, and by spring, the post office had been renamed. It took several years for the local railways to adopt the new moniker.

Within weeks of the incorporation, Henry Pratt moved to New York to establish a national sales office. Levi Gunn stayed on in Greenfield to serve as treasurer and general manager. The New York office, located in the hardware district at 78 Beekman Street, opened in November of 1868 and was a modest affair soon outgrown. The following year, the company moved to 87 Beekman Street where it shared an office with the firm of E. M. Boynton, the manufacturer of the Lightning Cross Cut Saw—a tool advertised as enabling two men to cut off a twelve-inch sycamore log in eight seconds.

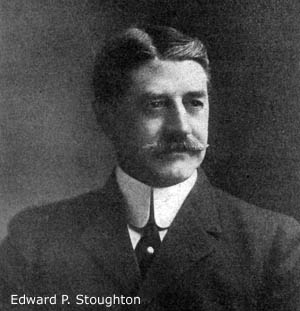

While still at the first address, Pratt hired Edward P. Stoughton to assist in managing the office. Stoughton proved an excellent hire. Diligent and quick to learn, he soon became the firm’s international sales representative. His interest in overseas markets enabled the company to export tools in substantial numbers surprisingly early in its history. Within a decade, the firm would boast of having penetrated one of the toughest markets of all—it was exporting large numbers of tools to Sheffield, England, the edge tool capital of the world.

Charles Amidon departs

Charles H. Amidon, Gunn’s longtime partner, left the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company in early 1870. He purchased a waterpower right from his former associates and began the construction of a small, two-story brick factory along the company’s canal. To help capitalize the new enterprise, he took on a partner, and before long, the firm of Amidon & Fisk was engaged in the business of manufacturing baby carriages. In 1871, Amidon had an unfortunate falling out with Millers Falls Manufacturing when the firm sued him for $1,000 to cover the non-payment of goods received. Although he maintained the goods were due him as salary for work done when superintendent, there must have been some merit in the Millers Falls complaint; Amidon paid $750 to settle the suit. By 1873, he had formed the Amidon Manufacturing Company. (Its relationship to Amidon & Fisk is unclear.) Located in Erving, Amidon Manufacturing was involved in the production of bit braces until its bankruptcy in 1877. When the business failed, Amidon relocated to Buffalo and became involved in a series of partnerships concerned with the production of bit braces. These included: Saxton & Amidon (1877-1883), Amidon & White (1883-1887), Amidon & Bastedo (1887-1890), and the Amidon Tool Corporation (1894-1898). A better inventor than businessman, Charles Amidon held over a dozen patents for bit braces but never experienced the financial success enjoyed by his former partners.(7)

Edward Lester, a talented employee of the Greenfield firm Nims & Pratt, replaced Amidon as plant superintendent. Nims & Pratt manufactured a brace developed by Clemens B. Rose, the proprietor of a small factory in Sunderland who patented a bit stock with ring-type chuck and metallic head in 1867 and a rotating brace handle eighteen months later. The Bit Stock Company, a Greenfield firm of undetermined ownership, began manufacturing Rose's brace.(8) Evidence suggests the Bit Stock Company was operated by Nims & Pratt, for in spring of 1869, the Greenfield Gazette and Courier reported the Rose Bit-Brace Company had filed a lawsuit against the partnership.

Edward Lester, a talented employee of the Greenfield firm Nims & Pratt, replaced Amidon as plant superintendent. Nims & Pratt manufactured a brace developed by Clemens B. Rose, the proprietor of a small factory in Sunderland who patented a bit stock with ring-type chuck and metallic head in 1867 and a rotating brace handle eighteen months later. The Bit Stock Company, a Greenfield firm of undetermined ownership, began manufacturing Rose's brace.(8) Evidence suggests the Bit Stock Company was operated by Nims & Pratt, for in spring of 1869, the Greenfield Gazette and Courier reported the Rose Bit-Brace Company had filed a lawsuit against the partnership.

The editor of the Greenfield paper didn't have all the facts. Three weeks earlier, the Boston Daily Advertiser reported Roberts & Stockbridge, a Northampton entity whose principals included brace inventor Charles H. Stockbridge and Osmore O. Roberts, had filed suit against Nims & Pratt over the right to manufacture braces based on the Rose patents. Documents relating to the lawsuit have not been located, but when the dust settled, Nims & Pratt was manufacturing Rose braces. The issue became moot when Nims & Pratt employee Edward Lester acquired the Rose patents and sold them to the Millers Falls operation in the summer of 1869. Production of the Rose brace continued at the Nims & Pratt factory until the new Millers Falls plant came online. The major player in Nims & Pratt was the prominent Greenfield businessman William Newton Nims. Given the close relationship between Nims & Pratt and Millers Falls Manufacturing, it is likely W. Newton Nims's partner was none other than Henry L. Pratt.(9)

Goodell, Sawyer, Dolan

Charles Amidon’s departure did little to impede product development at the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. In 1870, the operation purchased the small business operated by Albert D. and Henry E. Goodell. The men, brothers, had started a manufactory in 1866 on the banks of the Clesson River in the nearby town of Buckland. Located in the Perry & Demming building, the enterprise first made pieces for wooden chairs but switched to the manufacture of hardware items in 1868—the year Albert patented a brace with a ring-type chuck and pivoting jaws. The Goodell brothers became employees of Millers Falls Manufacturing at the time of the sale, and their new employer began producing the Goodell brace. Albert Goodell would eventually replace Edward Lester as of plant superintendent and embark on a distinguished career in tool design and manufacture—developing a number of highly successful tools for the Millers Falls Company before leaving in 1888 to found Goodell Brothers with his brother Henry.(10)

Charles Amidon’s departure did little to impede product development at the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. In 1870, the operation purchased the small business operated by Albert D. and Henry E. Goodell. The men, brothers, had started a manufactory in 1866 on the banks of the Clesson River in the nearby town of Buckland. Located in the Perry & Demming building, the enterprise first made pieces for wooden chairs but switched to the manufacture of hardware items in 1868—the year Albert patented a brace with a ring-type chuck and pivoting jaws. The Goodell brothers became employees of Millers Falls Manufacturing at the time of the sale, and their new employer began producing the Goodell brace. Albert Goodell would eventually replace Edward Lester as of plant superintendent and embark on a distinguished career in tool design and manufacture—developing a number of highly successful tools for the Millers Falls Company before leaving in 1888 to found Goodell Brothers with his brother Henry.(10)

Samuel Sawyer, the millwright who supervised the construction of the plant and dam for Millers Falls Manufacturing, elected to remain in the area after the project was completed. A one-time employee of the turbine-manufacturer Hunt, Waite & Flint, Sawyer decided to lease the sawmill owned by Millers Falls Manufacturing and install one of his former employer’s turbines to power it. His operation engaged in custom sawing and millwork fabrication. In 1871, he developed a new method for attaching the revolving head of a carpenter’s brace to a metallic frame and assigned the rights to Millers Falls Manufacturing. The patent was issued on the same day as that of William H. McCoy, a Millers Falls employee who invented a non-splitting wrist handle featuring metallic inserts. The company would use Sawyer’s design to attach heads to its better braces until the development of ball bearing heads rendered it obsolete; McCoy’s wrist handle would remain viable into the twentieth century. Samuel Sawyer eventually accepted a job as a wood turner at the Millers Falls plant, and William McCoy went on to develop a drill chuck, a set of spring-type brace jaws and an adjustable angular bit stock for the company.(11)

On January 17, 1871, William P. Dolan (also spelled Dolin) of Charlottesville, Virginia, patented a ratcheting brace that allowed a user to bore a hole without completing a full rotation of the handle. Although Dolan’s was not the first ratchet brace, his use of two opposing, spring-loaded pawls to control the direction of a brace’s rotation was a breakthrough. Millers Falls Manufacturing acquired the rights to his invention and made substantial changes to it—substituting one ratchet wheel for Dolan’s two and adding a ring shifter to engage and disengage the pawls. The Millers Falls adaptation of Dolan’s idea, with its two-pin ring shifter, may have been the most significant development in the history of the American ratchet brace. The centrality of his contribution to the arrangement is evidenced by the firm’s stamping the date of Dolan’s patent on its earliest ring-shift, pawl-type braces. The design, which leaves the front part of the ratchet wheel exposed, came to be used on more braces than any other and remains in production today. Four months after the Dolan patent was issued, John T. Lynam of Jeffersonville, Indiana, patented a single ratchet-wheel brace that used opposing leaf-type springs as pawls. Although Millers Falls Manufacturing thought enough of Lynam’s design to manufacture it, the brace never caught on.(12)

Those who had early on invested in the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company were well rewarded for their risk. Despite the costs of developing the site and building a factory, the Board of Directors declared a ten-percent shareholder dividends for calendar years 1870 and 1871. The new plant operated day and night, employing some sixty hands and turning out between 10,000 and 15,000 braces per month. The need for additional space soon became evident, and in 1872, the company completed construction of a brick addition with a slate roof. The new wing was parallel to the main building, one hundred feet long and forty-five feet wide. By the end of the year, employment had grown to 100 hundred hands, and development along the company’s canal proceeded apace with a building contractor, a vise company and a plane iron manufacturer joining Amidon’s baby coach factory.(13)

Those who had early on invested in the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company were well rewarded for their risk. Despite the costs of developing the site and building a factory, the Board of Directors declared a ten-percent shareholder dividends for calendar years 1870 and 1871. The new plant operated day and night, employing some sixty hands and turning out between 10,000 and 15,000 braces per month. The need for additional space soon became evident, and in 1872, the company completed construction of a brick addition with a slate roof. The new wing was parallel to the main building, one hundred feet long and forty-five feet wide. By the end of the year, employment had grown to 100 hundred hands, and development along the company’s canal proceeded apace with a building contractor, a vise company and a plane iron manufacturer joining Amidon’s baby coach factory.(13)

Backus Vise Company

The Backus Vise Company, an entity holding the rights to several bench vises developed by Vermont-born Quimby S. Backus, began renting space and waterpower at the Grouts Corner plant in 1870. Originally located in Windsor, Vermont, the vise company’s move to the Millers Falls canal owed much to the fact that Henry L. Pratt and Levi J. Gunn had become major investors and served as the Backus organization’s President and Secretary. Quimby Backus and Moses Newton, the Backus Vise Company’s treasurer, moved to Grouts Corner along with the operation. The relocated enterprise leased space in the Millers Falls boiler room and began construction on an adjacent wooden building to house its forging, polishing, and packing operations.

The Backus Vise Company, an entity holding the rights to several bench vises developed by Vermont-born Quimby S. Backus, began renting space and waterpower at the Grouts Corner plant in 1870. Originally located in Windsor, Vermont, the vise company’s move to the Millers Falls canal owed much to the fact that Henry L. Pratt and Levi J. Gunn had become major investors and served as the Backus organization’s President and Secretary. Quimby Backus and Moses Newton, the Backus Vise Company’s treasurer, moved to Grouts Corner along with the operation. The relocated enterprise leased space in the Millers Falls boiler room and began construction on an adjacent wooden building to house its forging, polishing, and packing operations.

The Backus operation was never large. Employment varied between sixteen and twenty-five. Under the supervision of Frederick Hubbard, the small, but productive workforce manufactured a line of products ranging from diminutive hand-held vises to 168-pound blacksmith models. The depth of its product line was due, in part, to its acquisition of the patents held by the Union Vise Company, a Boston-based maker of over forty styles and sizes of vises destroyed by fire in 1871. As Backus Vise had no foundry, rough castings for its products were purchased from the Clark & Chapman Machine Company in Turners Falls and finished locally. The vise company also served as a sales agent for Stratton Brothers, a manufacturer of high-end brass-bound wooden levels located in Greenfield. When the Millers Falls Company absorbed Backus Vise in 1873, the agency transferred to the new entity.

Misfortune plagued the Backus Vise Company. In December 1871, production came to a standstill when a fire burned out the part of the operation housed in the Millers Falls boiler room. A year later, the vise company’s new wooden building burned to the ground. Since demand for the vises exceeded capacity, The Millers Falls Manufacturing Company overlooked the problems of its tenant and installed yet another Hunt, Waite & Flint turbine to power the growing Backus operation. In spite of near-constant woe, Backus Vise managed to award its investors ten-percent dividends. In January 1873, the vise company merged with its larger neighbor to create a new entity, the Millers Falls Company. Quimby S. Backus had already moved on. He left the area several months earlier to begin manufacturing a series of tools he had patented the previous year. The boards of Millers Falls Manufacturing and Backus Vise merged the entities to reduce the expenses inherent in running separate operations, and while Frederick Hubbard, the vise company’s superintendent, became a director of the new company, Quimby Backus did not.(14)

As separate entities, neither the Millers Falls Mfg. Company, nor the Backus Vise Company, found it feasible to conduct a foundry operation. The situation changed with the merger, and in May 1873, the company construction on a foundry unit. The Backus vises represented an excellent addition to the Millers Falls product line—far more in keeping with the company’s basic business than the quilting frames, toy cannons, bowling pins, kites, and fifes the firm would add to the catalog. With its line of braces, vises, tool holders, family tool chests, and bracket saws, the company was well on its way to becoming a diversified manufacturer of hand tools. In 1873, the newly named Millers Falls Company moved its New York sales office to 78 1/2 Beekman Street. It would soon occupy enough of the building to drop the “half” from its address. In spring of 1876, the office would relocate yet again, to 74 Chambers Street.

Illustration credits

- Pratt & Stoughton portraits: Hardware Dealers Magazine, v. 43, no. 253, January 1915.

- Rose & Goodell braces: author’s photos.

- Plant 1873: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Map: F. W. Beers and G. P. Sanford. Atlas of Franklin Co., Massachusetts: from Actual Surveys. New York: F. W. Beers & Co., 1871.

- Linked ring-type chuck: author’s photo.

References

- Although Gunn is sometimes considered to have been the first president, Pratt’s position is listed in the notice of incorporation published in the Gazette and Courier.

- Map of Lands and Water Power for Sale by Oliver and James Moore, Erving and Montague, Mass.: Surveyed and Plotted by Jas. Stevens, Engineer & S. Moore, C. Surveyor. Hartford, Conn.: E. B. & E. C. Kellogg, July 1856.

- Old Sturbridge Village. Oliver Moore Collection. No. 1974.1.1.3.160.

- James Moore died tragically in June of 1869, entangled in the reins of a team of runaway horses.

- Old Sturbridge Village. Oliver Moore Collection. No. 1974.1.1.3.161.

- “A Destructive Fire in Greenfield.” Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) January 4, 1869.

- Information on the baby carriage factory and the lawsuit: Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 27, 1871, and December 4, 1871. Amidon’s Buffalo activities: Frank Kosmerl. “Buffalo Bit Brace Makers.” Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, v. 45 no. 4, p. 101.

- The brace Rose patented in 1867 was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 63,944. The sweep handle: United States Letters Patent No. 82,251.

- The lawsuit: “New England News.” Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, Mass.) March 19, 1869; “Greenfield Items.” Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) April 26, 1869. Lester and the patent transfers: “Greenfield Items.” Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) June 28, 1869, and August 16, 1869.

- Goodell’s brace was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 79,825. On the first Goodell factory: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 325-326; “Buckland - Manufacturing Interests.” History of the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, Press of J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1879. vol. 2, p. 699.

- On Sawyer’s career: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 86-87. Sawyer’s brace head attachment was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 118,058. McCoy’s sweep handle was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 118,039.

- Dolan’s ratchet was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 110,960. Most early Millers Falls ratchet braces are stamped on the shell with the date of the patent. His patent is also referenced in the 1878 company catalog. Lynam’s ratchet was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 113,680.

- An 1871 map of Millers Falls shows that in addition to the baby carriage factory, two other businesses bearing the name Amidon were located downstream from the Millers Falls factory on the mill canal. The firm of Amidon & Newton did at least some manufacturing but also contracted for carpentry and construction work. Solomon Amidon, one of the principals, was Charles H. Amidon’s older brother. (Another brother, William also lived in the village at this time.) The third Amidon firm, Amidon & Cobb, made hand plane irons. The Amidon involved with this firm has not been identified. See: F. W. Beers and G. P. Sanford. Atlas of Franklin Co., Massachusetts: from Actual Surveys. New York: F. W. Beers & Co., 1871. The statistics and the new wing: Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) 1870-September 1873.

- Thanks to Kendall H. Bassett for providing information on the officers of the Backus Vise Company via the firm’s letterhead. Fred C. Hubbard. Letter to Messrs. Norris H. Bragg & Sons, May 27, 1871. Other information about the Backus Vise Company in its Millers Falls location: Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) 1870-1873.